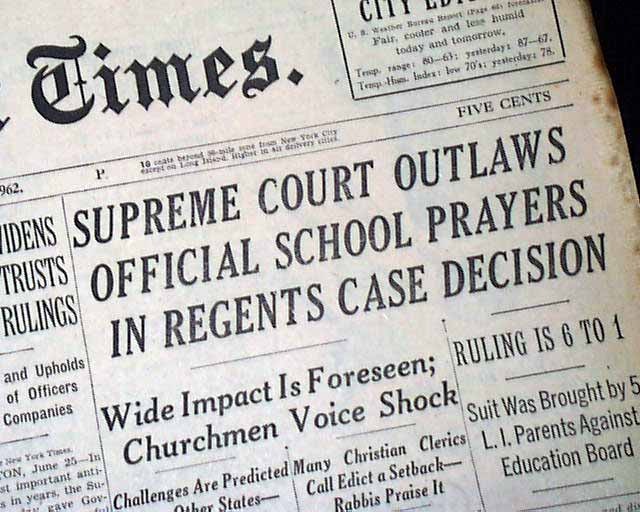

Engel v. Vitale, 370 U.S. 421 (1962)

Engel v. Vitale was a landmark Supreme Court decision in 1962. The case began in New York, where the state had created a prayer which was to be voluntarily read by students at the start of the school day. In the town of New Hyde Park, a group of families (including Steven Engel) opposed this prayer, so they sued William Vitale, the school board president. The case was first taken through the New York State Supreme Court, then the Appellate Division of the New York Supreme Court, and finally to the New York Court of Appeals, the highest court in New York. All three of these courts ruled that, since the prayer was voluntary, it was not in violation of the Constitution. The plaintiffs then took the case to the Supreme Court. The case was won by the plaintiffs in a 6-1 ruling. Engel v. Vitale was won by the plaintiffs because of the liberal Supreme Court, the First Amendment, and the Fourteenth Amendment.

The composition of the Supreme Court aided the success of the plaintiffs in Engel v. Vitale. The court at the time of the decision included Justices Black, Douglas, and Brennan, who along with Chief Justice Earl Warren created a strong liberal bloc. The Warren Court, in fact, was known for making decisions which were significantly more liberal than previous courts and those since. In the decision in Engel v. Vitale, those four Justices were joined by Justices Clark and Harlan, while the lone dissenter was Stewart. Given that the three New York courts had ruled in favor of the defendants, it seems likely that a conservative court could have ruled differently on this case.

The First Amendment is the amendment which is most applicable to Engel v. Vitale, and the one which was omnipresent during the case. The relevant two clauses state, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof” (US Const. amend. I). This applies to the case because the law created respects religion due to the fact that the prayer was created and sponsored by the state. Since that is in violation of the First Amendment, that would make the state sponsored prayer unconstitutional--if it were a federal law. The limitation of the First Amendment is that it only limits Congress, so on its own it would not be able to decide this case. However, another amendment provides what the First is lacking.

The Fourteenth Amendment is the other amendment which applies to Engel v. Vitale. In section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment is the clause, “no state shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States.” Since the rights given in the First Amendment constitute as “privileges or immunities,” because of the Fourteenth Amendment those rights (i.e. freedom from laws respecting the establishment of religion) apply on the state level as well. This means that the law created by New York is in violation of the Constitution.

Engel v. Vitale is an important decision in the U.S. today. For one, many other cases, such as Abington School District v. Schempp and Wallace v. Jaffree, which further limited school prayer. Additionally, the same reasoning used in this case also can apply to a major issue today. The problem of religious scenes displayed in government buildings has been subject to significant debate recently, and the same clauses which were applicable in Engel v. Vitale can apply here. Showing religious scenes in government buildings implies that the government is endorsing religion. Because of the First and Fourteenth Amendments, the endorsement of religion by state governments is in violation of the Constitution. It follows that it should not be allowed to display religion in government buildings.

United States v. Lopez, 514 U.S. 549 (1995)

United States v. Lopez was an important Supreme Court decision from 1995. The case was started when student Alfonso Lopez brought an unloaded gun to school. Lopez was arrested for violation of the Gun-Free School Zones Act (GFSZA). Because the act was a federal law, he was tried in a federal district court. In his trial, Lopez argued that the GFSZA was unconstitutional because is was not within Congress’ power to regulate guns in schools. The district court (W.D. Tex.) ruled that the law was within Congress’ power and that Lopez was guilty. Lopez then appealed the decision, which went to the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals. The Fifth Circuit ruled that Lopez was not guilty because the GFSZA was not within Congress’ power to enforce. The prosecution then appealed to the Supreme Court, where the case was won by the defendant in a 5-4 ruling. The most applicable portion of the Constitution to U.S. v. Lopez is Article 1, Section 8, while the conservative court was the greatest factor in the victory of the defendant due to the strict interpretation of the section.

The conservative Supreme Court was a significant factor in the outcome of the case. Chief Justice William Rehnquist was a staunch conservative who opposed giving much power to the federal government. At this time, the justices on the court were also becoming more polarised; Justices Scalia, Kennedy, O’Connor, and Thomas often joined Rehnquist in the conservative lane, while Souter, Ginsburg, Breyer, and Stevens formed a liberal bloc. Because the case’s main focus was simply how much power Congress could have, it was not surprising that the Justices fell into their lanes on this decision. Because of this, the court makeup had a drastic influence on this case--if there had been one more liberal Justice, the case might have gone to the prosecution.

The section of the Constitution most relevant to U.S. v. Lopez is Article 1, Section 8. This section outlines the powers allotted to Congress. The third of these powers is often referred to as the “Commerce Clause,” and states, “[Congress has the power] to regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes” (US Const. art. 1 §8). Looking at this clause from a strict interpretation, it is easy to see how the regulation of school zones would not be sanctioned by this clause. This is the interpretation which ruled the GFSZA unconstitutional, and why the defendant won.

However, the dissent had a different view on how this clause affected the case. The dissenting opinion was that violence in schools applies to commerce, because violence can lead to poorer education which can significantly affect interstate commerce. As such, under this view, the Commerce Clause would actually sanction the GFSZA, since the act’s provisions would affect commerce.

The debate over the interpretation of this clause is more relevant now than ever. This is because the effect of mass shootings in schools is growing every year as more and more of them occur. One solution to this problem would be for Congress to ban certain kinds of weapons, but that ability is not explicitly given to Congress. However, if the Commerce Clause is looked to, then using the same arguments as the dissent in U.S. v. Lopez, there can be justification for passing such laws.

Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission, 558 U.S. 310 (2010)

Citizens United v. FEC was one of the most important Supreme Court decisions in recent history. The beginning of this case was when conservative corporation Citizens United released the film Hillary: The Movie, which aimed to criticise Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton. The Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act (BCRA) disallowed “electioneering communications” within 30 days of a primary election, and the film was counted as “electioneering communications.” Before being penalized, Citizens United declared that the BCRA was unconstitutional and took the argument to the federal district court D.D.C. D.D.C. ruled in favor of the defendant, and the plaintiff took the case to the Supreme Court. The case was won by the plaintiff in a 5-4 ruling. Citizens United v. FEC was won by the plaintiff because of a very conservative court and controversial use of the First Amendment, the most applicable section of the Constitution in this scenario.

The composition of the Supreme Court was a major reason for the ruling in favor of the plaintiff. Although Chief Justice John Roberts was not as conservative as Rehnquist, the conservative bloc on the Roberts court was nearly impenetrable: Scalia, Thomas, and Alito were all nearly guaranteed to take the conservative position on heavily debated issues. Meanwhile, Justices Ginsburg, Stevens, Breyer, and Sotomayor were reliably liberal votes. Often the “swing” vote was Anthony Kennedy, but though he sometimes sided with the liberal bloc on social issues, when it came to economics, he was also very conservative. Because of how polarised the Supreme Court had become, the result of Citizens United v. FEC was very predictable--anything else would have been anomalous.

In Citizens United v. FEC, once again, the First Amendment assumed an important role. The plaintiff argued that spending money on “electioneering communications” is a form of free speech, and is protected under the First Amendment. More controversially, the plaintiff argued that, since a corporation (such as Citizens United) is merely a group of people, a corporation should be counted as a person and therefore given the same rights as citizens. The clause in question states, “Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech” (US Const. amend. I). Since BCRA is a Congressional law, and it allegedly abridges the freedom of speech, it would be banned under the Constitution.

However, the application of the First Amendment in this way is troubling. The issue is that, unless the definition of a person in the Constitution is limited to single persons, the way is paved for massive power imbalances. Those who control one or more corporations would essentially be more than one person, so they would wield not just greater economic power but also greater legal power. The Constitution, which was designed and modified so that people would have equal rights, would become a vessel for promoting unequal rights among Americans. It follows that the First Amendment ought not to treat corporations as persons, in order to uphold the ideals of political equality.

The legacy of Citizens United v. FEC can be seen everywhere in politics--political action committees, or PACs. Due to the ruling, PACs can receive unlimited money and spend it on political advertising. The prominence of PACs in politics has become a contentious issue, and the same logic applies to it as applies to Citizens United v. FEC. The decision has changed the political landscape for years to come.

Comments

Post a Comment